Yosemite is considered by many the crown jewel of America’s national parks. From the high country where glacier-girded peaks kiss the sky to Yosemite Valley where 2,000-foot waterfalls send plumes of mist that swirl around awestruck visitors, this marvel of nature has remained an unspoiled destination for nearly 150 years.

Yet exactly how Yosemite has remained so pristine is a little-told story. It begins at the turn of the 20th century as word was getting out and the park was transitioning to public land. The stars of the story were a troop of unflagging African Americans who were called upon to safeguard these mountain cathedrals so future generations could someday experience their majesty firsthand. These park protectors were known as the Buffalo Soldiers, and their legacy lives on to this day.

The Early Black Regiments

After the Civil War, where approximately 180,000 African American soldiers fought in the Union’s campaign to end slavery, Congress passed the Army Reorganization Act (1866). Necessary for everything from keeping the peace at home to rebuilding a war-torn country, the Act doubled the size of the United States Army and by 1869 it included four African American units “” the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Thus began the tenure of our nation’s first professional black soldiers.

In the South (and the North, for that matter), newly freed African Americans had to make a decision: endure racism at home where there was little opportunity for good jobs, or take their chances joining the military which had its own inherent risks. Many chose the latter, and enlisted.

The units were segregated, but afforded steady pay, and they fought in a number of conflicts including the Spanish-American War in Cuba, the Philippine Insurrection and the Indian Wars during America’s expansion across the western frontier. It was here that the name Buffalo Solider was coined. The Native Americans thought the black soldiers’ hair was similar to the hair between the horns of the many buffalo that roamed the plains.

The Buffalo Soldiers in National Parks

America’s unique commitment to developing the first national parks (a model that has now been copied worldwide) created its own unique challenges: mainly, how to protect the newly designated public lands. The solution? Deploy the Buffalo Soldiers.

Between 1891 and 1913 “” before the establishment of the National Park Service “” the U.S. Army acted as the official administrator of both Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. This tour of duty took a historically significant turn in 1899, when approximately 500 Buffalo Soldiers departed from the Presidio along the still bridge-less Golden Gate in San Francisco, and rode around the Bay, through the Central Valley and up into the beautiful Sierra Nevada mountains. Their destination was Yosemite, a prized assignment which was considered within the ranks to be the “Cavalryman’s Paradise.”

Once there, the Buffalo Soldiers were tasked to protect Yosemite (and nearby Sequoia National Park) from a variety of threats “” poaching of wildlife, illegal logging and destructive livestock grazing to name a few “” not to mention the building of infrastructure which included roads and trails that are still in use today.

With the memory of slavery still fresh at the turn of the 20th century, and with many former slaves and even some slave owners still alive, the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers were even more remarkable. In addition to their role as official park protectors, here are a few of their notable achievements :

- Created an arboretum along the South Fork of the Merced River in Yosemite near today’s Wawona. Widely considered the first marked nature trail and museum in a national park. (1904)

- Constructed the first usable wagon road into the Giant Forest of Sequoia National Park. Some of the oldest, largest trees on the planet. (1903)

- Cut a trail up rugged Mt. Whitney; at 14,505 feet, the tallest peak in the contiguous United States. (1903)

- Served as official escort from San Francisco to Yosemite for President Theodore Roosevelt’s historic visit. The 9th Cavalry had the honors, led by Captain Charles Young. (1903)

Notable Buffalo Soldiers

The contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers perfectly embody our national motto “E Pluribus Unum.” Out of many, one. While the efforts of these African American patriots are finally getting the recognition they deserve, there are some whose inspired deeds will never be forgotten.

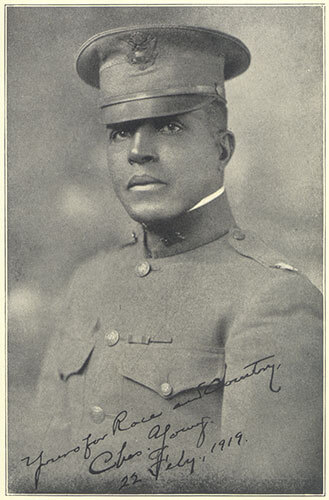

Colonel Charles Young (1864-1922)

Born into slavery in Kentucky, Charles Young excelled after the Civil War with his newfound freedom. He was the first African American to graduate from an all-white high school in Ripley, Ohio, then went on to become just the 3rd African American to graduate from the esteemed West Point military academy (though his tenure there was marked by unrelenting racism from other cadets).

As Captain of Troop I in the 9th Cavalry, Young was the highest-ranking African American officer in the U.S. Army and led his Buffalo Soldiers from San Francisco to Yosemite for their stint as protectors of the national parks. He was moved by the natural beauty he encountered, claiming that the Sierras “will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains.”

In addition to directing Troop I’s protection mission, Young was a lover of ecology and made suggestions to the Department of Interior on how to preserve native flora and stop erosion of hillsides. It was also reported that no instances of poaching occurred on Young’s watch, and he initiated negotiations with private landowners surrounding the park to sell their acreage to the government to provide more room to roam for future visitors. By 1903, Young was named Superintendent of nearby Sequoia National Park, the first African American to hold such a title.

After serving as Superintendent, Young continued his military career by fulfilling posts in Haiti, Liberia and Nigeria, not to mention seeing combat against Pancho Villa’s troops during the Mexican Expedition of 1916. His tenure, however, was marked with the stain of racism. Young was unfairly turned down to lead troops overseas in WWI. The decision cited health reasons and involved President Woodrow Wilson himself, but the real reason was something much more insidious “” they were not interested in a black man commanding white troops, and had Young served in this capacity he would have been eligible for a promotion to Brigadier General. Not allowed to join the war effort, Young remained engaged by teaching military science at Wilberforce University through 1918 but he would not be denied. Demonstrating his classic grit, Young responded to his medical discharge by riding 500 miles on horseback from Ohio to Washington, D.C. thus proving he was fit for service. Young was reinstated as Colonel, overcoming his unfair treatment, and reassigned as military attaché to Liberia.

Colonel Young died in 1922 while serving in Nigeria, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full honors. Years prior, during his impressive stint at Sequoia National Park, the thankful locals wanted to pay homage to Young by naming a tree after him. In an act of humility, he insisted they wait 20 years to see if they were still interested.

Wait, they did. In 2004, nearly 100 years later, his hard work was memorialized with the dedication of the Colonel Charles Young Tree. Having stood tall and resilient for thousands of years, the tree is symbol of his enduring legacy.

Park Ranger Shelton Johnson

Though over a century later, Park Ranger Shelton Johnson has gained national adoration for his efforts to bring the Buffalo Soldiers to life. From educating countless visitors about the contributions of African Americans to the history of this nation, to his tireless work as park protector of our public lands, Ranger Johnson’s legacy is woven forever into the mystique of Yosemite National Park.

Born in Detroit, young Shelton Johnson first experienced the grandeur of nature while living in Germany where his father was stationed in the Army. A family trip to the Berchtesgaden Alps made a strong impression, with their awe-inspiring sawtooth peaks set against deep blue sky. Worthy of preservation themselves, these mountains would later become Berchtesgaden National Park in 1978.

Back home, Johnson continued his education and graduated from the University of Michigan in 1981. He served with the Peace Corps teaching English in Liberia, then returned from West Africa to get his M.F.A. in Creative writing with a focus on poetry. After working summers at Yellowstone, Johnson took a full-time job there as a ranger in 1987.

Once Ranger Johnson transferred to Yosemite, his career took off. He learned of the Buffalo Soldiers and was shocked that more people didn’t know their story and impactful history. Inspired, Ranger Johnson wrote and performed a living history through the eyes of Elizy Bowman, a Buffalo Soldier on the muster rolls for the 9th Cavalry. Deeply personal and powerfully portrayed, the performances will forever be a hit with visitors to Yosemite.

Over his nearly 30-year career at Yosemite, Ranger Johnson’s achievements are wide-ranging. He has been a tireless advocate for increasing minority visitation to our National Parks, as well as inspiring African Americans to reconnect with the natural world. His appearance in the popular Ken Burns series, “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea“, captured the imaginations of many, including Barack Obama. Johnson discussed the series with the President during a preview at the White House in 2009.

Ranger Johnson’s background in creative writing has served him well. He is the author of the novel Gloryland, which filmmaker Ken Burns calls “a work of extraordinary imagination and sympathy, a journey from slavery to the mountaintop, perfectly realized.” It’s the story of Elijah Yancy who as a teen is exiled from the Reconstructed South and heads west, finding his calling as a Buffalo Soldier.

The Importance of the Buffalo Soldier Today

As some of the earliest stewards of our public lands, the Buffalo Soldiers historical importance cannot be underestimated. Their contributions to our National Parks occurred on the heels of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which upheld the concept of “separate but equal” thus propping up an ugly era of discriminatory Jim Crow laws. Yet despite these challenges, the Buffalo Soldiers fulfilled their duties with professionalism and precision.

Today, it’s essential that the story of the Buffalo Soldiers be widely told. As a means of inspiration, of pride, and of ownership. Like the song goes….this land was made for you and me.