For over 150 years, the Yosemite Firefall has possessed a “flare” for the dramatic. From the original man-made spectacle atop Glacier Point to today’s natural phenomenon along the ribbon cascade of Horsetail Fall, celebrating this festival of incandescence has long been a draw for visitors to Yosemite, not to mention an integral part of the Park’s history.

What Was The Original Yosemite Firefall?

Imagine this. You’re sitting around an outdoor stage at the base of a 3,000-ft cliff. The ranger wraps up his talk and the pianist begins to play a spirited version of “America the Beautiful.” A sing-a-long ensues, creating a sense of camaraderie among your fellow campers. Then, the moment everyone has been waiting for…

A hush as the audience looks skyward. Constellations twinkle peacefully against the blue-black canvas of the Sierra night sky. The scent of pine infuses the still summer air when out of nowhere a booming voice calls towards the heavens:

Hello, Glacier Point! Is the fire ready?

A faint voice calls back: The fire is ready!

Let the fire fall!

Suddenly, a “waterfall” of molten embers plunges over the granite precipice. The Firefall is at once a steady ribbon of flame and thousands of tiny, discernible sparks. After several dazzling minutes, when the last spark gives way to the night, the crowd goes silent having witnessed such an impossible display. Indeed, this mountain magic is what they called the original Yosemite Firefall.

How Did The Yosemite Firefall Originate?

Though some of the finer details have been lost to history, the original Yosemite Firefall can be attributed to the showmanship of a notable immigrant trailblazer by the name of James McCauley.

McCauley, a native of Ireland, first arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1868 and by 1871 had overseen the construction of the new Four-Mile Trail — a rugged set of switchbacks that to this day continues to connect the Valley to Glacier Point. This new “shortcut” opened up tourism opportunities atop the majestic precipice, and soon Glacier Point’s Mountain House hotel was opened in 1873, becoming a focal point of Yosemite lodging.

Looking to entertain the hotel guests, McCauley would build fires near the edge of the cliff. The excitement — and sense of danger — was hard to beat. A sign was erected, part tongue in cheek but also a necessary warning:

At the end of the campfire (in an act hard to imagine by today’s standards) the glowing embers were pushed over the cliff. Whether McCauley knew this “Firefall” would be a spectacle for those below is unsure. But word got out and soon he was taking “donations” from visitors in the Valley. The Firefall became a much-anticipated event.

Evolution of the Firefall

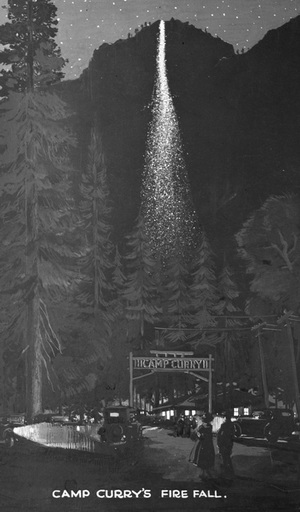

The McCauley era of the Firefall ran until 1897 when his lease expired at Mountain House and he was evicted by state commissioners in favor of the Washburn Brothers, rival owners of the Wawona Hotel in Southern Yosemite. The Firefall lay in limbo for several years until husband and wife concessioners David and Jennie “Mother” Curry established Camp Curry in 1899.

A collection of wood-framed tent cabins at the eastern end of Yosemite Valley, Camp Curry (today’s Curry Village) became a popular destination for the increasing number of visitors eager to experience Yosemite’s stunning rock and waterscapes. Guests soon began asking about the Firefall, and by the early 1900’s the tradition resumed with David himself using his booming voice to call up to the fire makers.

An outdoor stage complete with ranger talks and musicians provided entertainment, while the main attraction — the Firefall — flourished as the program finale. In 1917, the Mountain House gave way to a majestic new chalet. The Glacier Point Hotel brought more guests, and more synergy between the lodge above and Camp Curry below. That same year David fell victim to an infection and passed away at just 57, but his wife Jennie and son Foster — committed to carrying on their roles as dedicated hosts — kept the fire burning.

The Camp Curry era was a golden one. Hosting presidents, actors, and traveling families alike, it became a hub for Yosemite tourism. A song — the “Indian Love Call” — was incorporated into the proceedings, and the fires themselves became larger, using red fir bark known for its superior glow. Throughout the summer, the Firefall always occurred at 9 pm. Firsthand accounts stated that some guests were so overcome by the almost spiritual spectacle that they began to cry.

When Did The Original Firefall End?

With evolving emphasis on how to protect Yosemite’s natural wonders, the National Park Service ordered an end to the original Yosemite Firefall in the winter of 1968. The sheer number of visitors attempting to view the spectacle led to meadows being trampled, increased car traffic, and the persistent threat of fire in such a wooded environment. Ironically (or perhaps predictably) the Glacier Point Hotel burned down 18 months later. The last Firefall was on Thursday, January 25, 1968, thus ending its nearly 100-year run as a fascinating part of Yosemite history.

A Flame Rekindled: Today’s Firefall

In what can only be called a twist of fate, a new Firefall was “discovered” soon after the last embers of the original Firefall went dark. It was February of 1973 when famed mountaineer and adventure photographer Galen Rowell was driving west through Yosemite Valley. Glancing up, he saw the setting sun hitting Horsetail Fall in an otherworldly fashion. The thin cascade — a seasonal ribbon of water skirting down the sheer face of El Capitan — lit up in a fiery orange glow. He stopped to photograph the spectacle — a dagger of fire running down granite — and the rest, as they say, is history.

Today, the natural Yosemite Firefall occurs every February when the conditions are just right. Minimal cloud cover, the angle of the sun and the amount of water flowing all synchronize to create a worthy sequel to the original. With all its moving parts, the Firefall’s intensity changes by minute, hour, and day. The result is a prized reward: stunning photographs captured by professional and amateur shutterbugs alike.

How To Experience Today’s Firefall

Though a natural phenomenon, the increasing popularity of today’s Yosemite Firefall makes personalized trip planning (and respect for the fragile ecosystem) a necessity. Checking this year’s Firefall Reservations and Regulations is your first step, followed by finding nearby lodging that suits your taste and budget.

Whether camping or staying at a comfortable hotel, visitors should allot the necessary amount of time and pack the appropriate gear for winter travel. As a cherry on top of your Firefall experience, visit the Yosemite gateway town of Mariposa for tasty food, local shopping, and Gold Rush history. Here, the Mariposa Museum & History Center features a bonus: the original Firefall Horn that was once used to call back and forth between the dramatic clifftop of Glacier Point to the lush Yosemite Valley below.