For the curious traveler, the nexus between past and present is a compelling space. Visiting famed landmarks, learning about pivotal moments of local Mariposa County history, walking in the footsteps of those who came before…they all fuel one essential question: “what was life really like back then?”

The life and plight of the Chinese in Yosemite Mariposa County is a fascinating (and often challenging) tale. From the building of essential roads through the rugged Sierra Nevada to bustling Gold Rush-era Chinatowns and a chef whose cuisine was so memorable that they named a mountain after him, their enduring yet virtually unrecognized contributions are as old as the region itself. What’s even better? They can be explored with nothing more than a reliable set of wheels and a sense of discovery as the surrounding natural beauty of Yosemite Mariposa serves as your trusted co-pilot.

The Stage Is Set

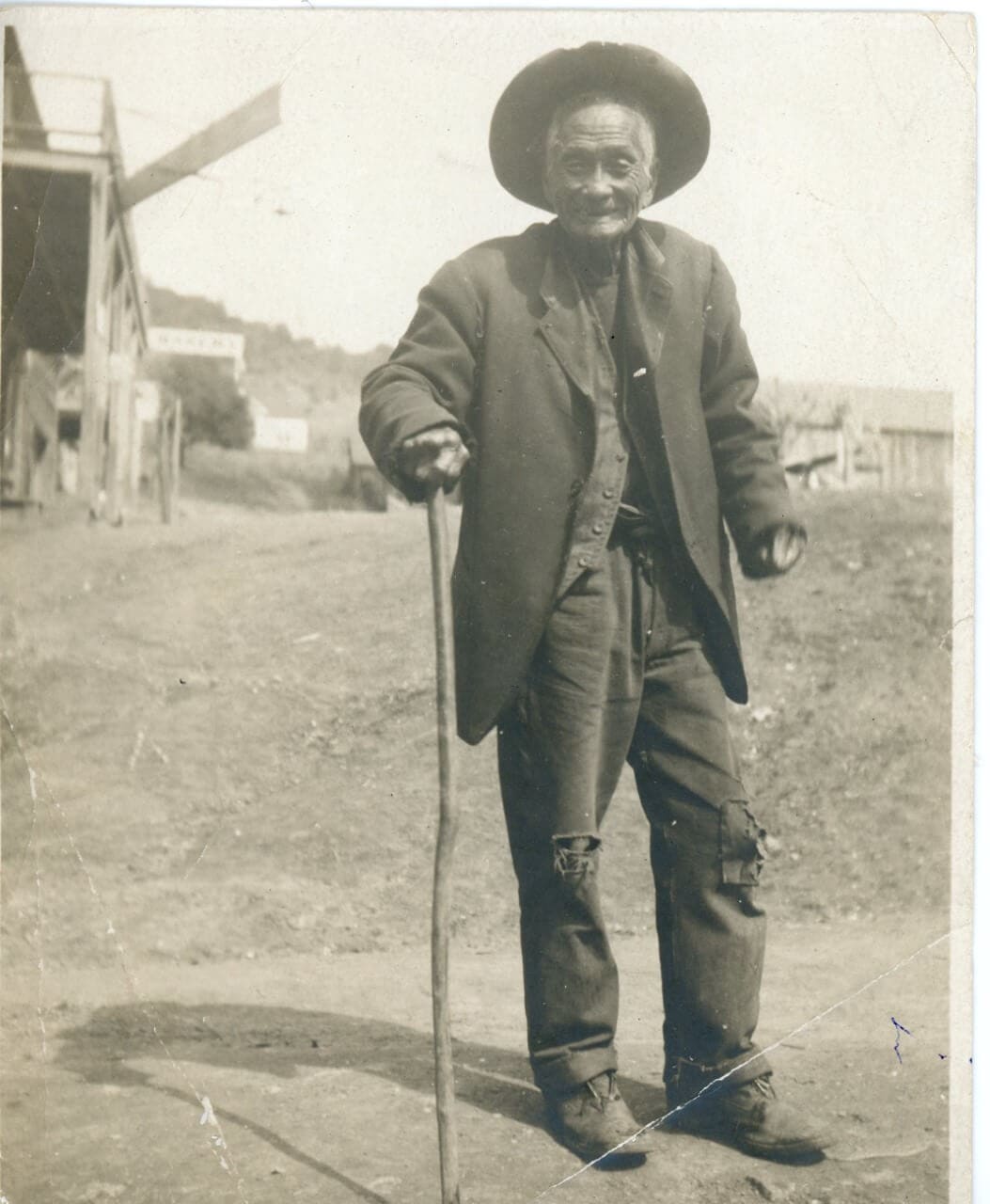

“China Frankie. One of three Chinese left in Mariposa when I was a little girl. Lee Gin and Ak Hi had restaurants. “Frankie” lived up the creek near Alarid’s in a tiny shack he built – mostly with flattened kerosene cans. Frankie had no visible means of support, though he always had a garden. We occasionally gave him a chicken or a pie or old clothing. Camin’s store on left behind him. School at top of hill.”

Photo courtesy: Mariposa History Museum

The mid-1800’s were desperate times in southeast China. Severe drought led to famine, thus forcing its citizens to abandon their homeland. As fate would have it, the booming California Gold Rush proved an enticing destination. With direct ship passages across the Pacific Ocean from China to San Francisco, travel to California from China was more direct and often easier than most pioneer travel across the US by land. First arriving in 1848, these Chinese immigrants came not only for survival but with dreams of striking it rich. However, they immediately found the deck stacked against them due to a series of recently passed laws.

The second half of the late 1800’s would have been a difficult time for any pioneering individual to settle in Mariposa County, but the odds were even further against the Chinese. Beginning with the Foreign Miners Tax of 1850 (which taxed Chinese miners $20 per month, approximately $500 in today’s dollars) and culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Chinese were both legally and socially ostracized.

In Mariposa County, early news articles (dated between 1850 and 1890) paint a picture for what life would have been like for the far east Asian immigrants. An 1858 story in the “San Joaquin Republican” blamed a fire that burnt down the town of Mariposa on a “dirty little Chinese house of ill fame’s religious practices”. Also in 1858, an article in the “San Francisco Daily Bulletin” tells of the citizens of Hornitos expelling a local Chinese encampment by setting fire to Chinese homes to force out the inhabitants. In 1886, the “Mariposa Gazette” wrote that an “Anti-Chinese Non-Partisan League” was formed with the goal of removing Chinese immigrants from Mariposa County. Its meetings were covered regularly.

Because of these societal and economic hurdles, the story of Chinese perseverance and success is even more incredible. Early Chinese immigrants had to rely on the wide range of skills they brought from home “” everything from construction, agriculture and textiles to traditional medicines and the culinary arts. Though the hill was steep, the Chinese in Yosemite Mariposa County persevered, and their legacy is now beginning to get the recognition it deserves.

Wawona

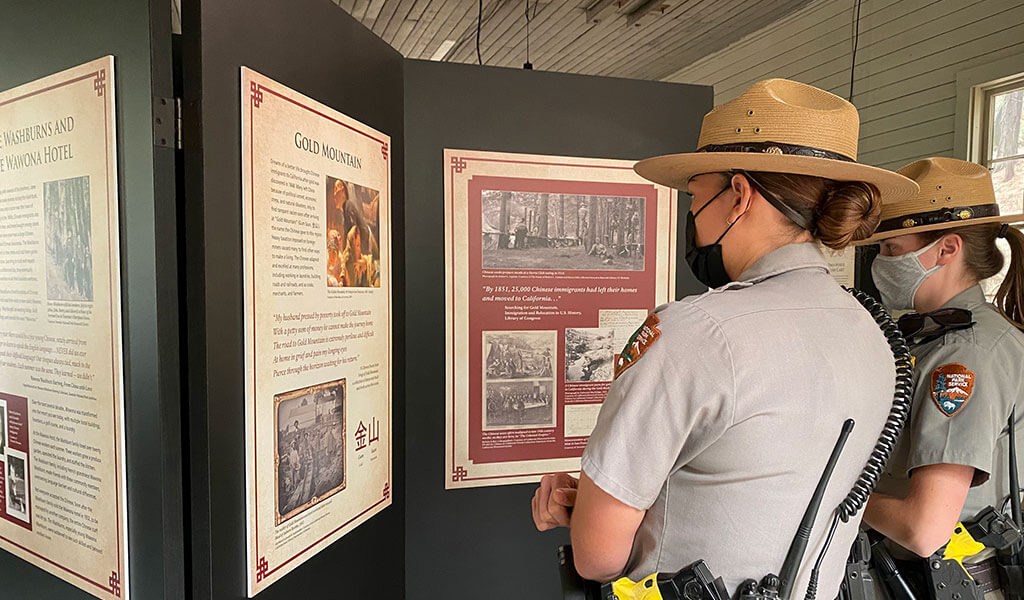

Located in the Southern Yosemite region of Yosemite Mariposa County, Wawona village is a focal point for learning about the Chinese experience in the Park and the American West writ large.

Built in 1917 and used to clean the large number of guest linens, the newly dedicated Chinese Laundry Building in the Yosemite History Center near the Wawona Hotel features exhibits detailing the many contributions of early Chinese immigrants such as the construction of 23-mile Wawona Road during the winter of 1874-1875. Completed in just four months using hand picks, shovels and wheelbarrows, the road connected the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias to Yosemite Valley thus providing improved access so visitors could come and enjoy the magical landscape.

Part of the renamed Yosemite History Center whose updated mission is to tell the full, multi-ethnic history of the Park, the Chinese Laundry Building had been used for storage for the nearby Wawona Hotel, but now has come full circle in representing the overlooked history of the Chinese in the area. Other exhibits include the notable culinary contributions of early “celebrity” chefs such as Tie Sing (see below) and Ah You, who served as head chef at the Wawona Hotel for 47 years.

Tioga Road

With its steady climb and unsurpassed mountain vistas, Tioga Road (Highway 120) is the backbone of the Northern Yosemite region. Though not a historical exhibit per se, the satisfaction derived from winding through its graceful alpine turns can be directly attributed to the Chinese workers who completed it in 1883.

Originally called the Great Sierra Wagon Road, the 56-mile stretch was commissioned by shareholders to crest the High Sierra at an elevation of over 10,000 feet and reach their silver mine in Bennetville. The call was answered by a gritty crew of Chinese laborers who worked relentlessly by hand without the use of horses or mules, often discharging dangerous powder to blast through walls of granite that blocked the route. What’s even more amazing is the amount of time they took to complete it…just 130 days! Interesting fact…the Bennetville mine went bust the following year but we still have the “silver lining” of Tioga Road as an enchanting Sierra crossing for visitors to Yosemite Mariposa County.

Coulterville

Mining roots run deep in Northern Mariposa County, and nowhere captures the Gold Rush spirit quite like Coulterville. With nearly as many California Historical Landmark buildings (40) as residents (60), Coulterville was once a boomtown that boasted the Mother Lode’s largest Chinatown.

For a broad overview and local color on the region’s hard rock history, visit the Northern Mariposa County History Center. Located at the foot of Coulterville’s highly walkable main drag (Greely Hill Road), NMCH features exhibits on John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt’s famous trip to Yosemite, as well the abandoned Sun Sun Wo Store. Built in 1851, the adobe and stone building is one of the earlier Gold Rush buildings still intact and survived three major fires in town. First opened by Mow Da Sun and his son, Sun Now, the general store operated successfully from 1851 to 1926.

Though no longer standing, the Big Gap Flume near the town of Buck Meadows was an amazing feat of Gold Rush engineering and built by Chinese workers on behalf of the Golden Rock Water Company. Completed in 1860, the flume was nearly a half-mile long and rose nearly 25 stories as it carried water across rugged Conrad Gulch to the mines and ranches below. There is a historical marker located along Highway 120 which details some of the history, but regrettably does not mention the substantial contributions of the Chinese to this engineering marvel.

Mariposa

The Chinese immigrants of the time settled in Mariposa around Mariposa Creek and in the nearby town of Aqua Fria, which at one time had a larger population than Mariposa before it burnt down. Due to the social climate of the time, some in the local Chinese community also tried to move south of Mariposa in what is now Mormon Bar to create a community of their own.

In 1858, it was estimated the Chinese living in the community of Mariposa numbered in the thousands, outnumbering white settlers 2-to-1. During that time a theatrical troupe made up specifically of Chinese settlers was formed to provide a form of entertainment to the large, growing populace.

Today, a great way to learn about the history of this one-time booming populace is to visit the Mariposa Museum and History Center in Mariposa where artifacts and the archives of the Mariposa Gazette paint the picture of what it would have been like during that time period.

Sing Peak

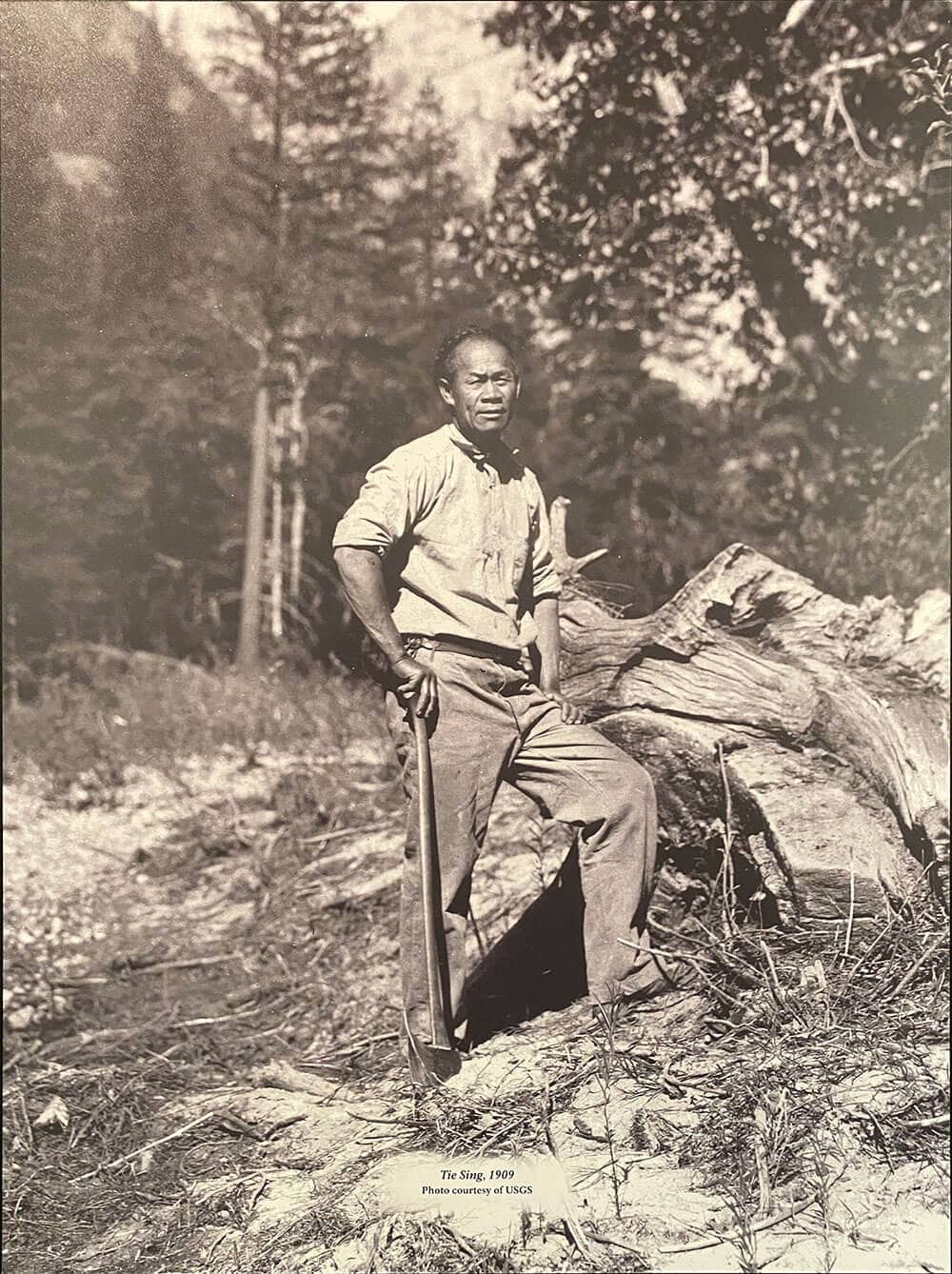

Located in southeastern Yosemite National Park on the border with Sierra National Forest, Sing Peak rises 10,552 feet above a cluster of granite-cradled pristine lakes. The peak is named after a man who could be considered one of the American West’s first “celebrity” chefs, Tie Sing.

Tie Sing was the cook for Robert Marshall (1867-1949), Chief Geographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and charter member of the Sierra Club. Able to conjure up amazing meals in the backcountry, Sing gained a reputation as “philosopher of the Sierra” and was tapped to add his culinary wizardry to the famous Mather Mountain Parties. Hosted by Stephen Mather, head of the newly formed National Park Service, the purpose of these parties was to convince his guests “” a collection of influential leaders from the private and public sectors “” to support the protection of federal lands.

Sing’s cooking was integral to the success of the Mather Mountain Parties, with journalist and attendee Robert Sterling Yard writing “…his astonishing culinary exploits have been more than I can quite believe…I shall not forget that dinner.” His backcountry cuisine required ingenuity such as preserving meat in wet newspaper and keeping sourdough bread starter next to the warm bodies of the mules as they traveled. Sing Peak was named in his honor in 1899, years before his passing in 1918. Living legend, indeed.

Credit Due

Chinese history breathes life into the glorious alpine passes, dusty backroads and boomtown sidewalks that form the unique tapestry of Yosemite Mariposa County. As we continue to explore and educate, a debt of gratitude is owed to the early Chinese pioneers and their resolute contributions to the Sierra experience we know and love today. Hopefully this awareness leads to further research, more visitors who want to walk in their footsteps, and the uncovering of more fascinating tales from the Gold Rush and beyond.